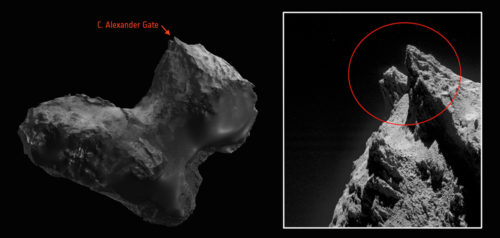

This series of images of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko was captured by Rosetta’s OSIRIS narrow-angle camera on 12 August 2015, just a few hours before the comet reached the closest point to the Sun along its 6.5-year orbit, or perihelion (credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

Last time I wrote, we were in summer approaching perihelion. Very soon after that post we released all the first lander results from the surface of the comet. I had mentioned the result regarding the comet’s magnetic field (or lack thereof) but other measurements were made. COSAC revealed a number of organics near the surface of the comet, some – methyl isocyanate, acetone, propionaldehyde and acetamide – that have never before been detected in comets. Through the deployment of the MUPUS hammer we found that the final landing site appeared to have a very hard subsurface layer. We also found from the CONSERT experiment that the head lobe of the comet is rather homogenous, at least down to 10m scales. We could also use CONSERT to get a better fix on the location of the lander, which we consider to be within a ~20x~30 m region.We are soon to have a large Astronomy and Astrophysics special issue released collecting many of the more detailed first results from the mission. There are 47 papers in the issue! So stay tuned for that. A number of the blog posts have detailed these results already. Last time I mentioned the role played by amateur astronomers, we had a dedicated post about the important role they play in the mission, in particular now, with the good viewing conditions we will have up to late spring 2016 I believe:

http://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/08/07/amateur-astronomers-keeping-an-eye-on-the-comet/

July 9th was the last contact we had with the Philae lander, after which time we moved further away from the comet for navigational accuracy reasons (as mentioned last time, the dust environment interferes with this). We hope that by late October, November this year we will get to ~200 km and altitudes within which the lander can get a signal to us. As promised a detailed blog post on the lander was posted, which details the most information we have on the status of the lander and is more than I can remember, so I link it here!

Perihelion

August saw perihelion , our closest approach to the Sun and it did not disappoint. In the months leading up to perihelion and following it, we have observed a number of large outbursts of material. In late July we had such an extreme outburst that the magnetic field that is “frozen in” to the outflowing solar wind was actually pushed away from the comet, forming a so called magnetic cavity out to the spacecraft around 184 km from the nucleus. We also detected an increase in a number of volatiles (gases) during this period, suggesting a large excavation and emission of subsurface material may have occurred. We are looking forward to getting back close to the comet to observe any changed in the comets surface.

http://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/08/11/comets-firework-display-ahead-of-perihelion/

Some of you asked about me and heavy metal. Something cool happened in summer, I got an award! check out around 16:00 on this youtube video.

Brian May has also been doing some work on the Rosetta images –

http://brianmay.com/brian/brianssb/brianssbaug15.html

http://brianmay.com/brian/brianssb/brianssbsep15a.html#14

It was with great sadness that we lost a great friend and colleague, Dr Claudia Alexander. She was the NASA Rosetta Project Scientists, my counter part on the US side and someone who had helped me greatly since I cam onboard the mission in 2013. She is very much missed by the Rosetta family, and as a mark of this, we identified a gate like structure on the comet and named it after her, the “Claudia Alexander Gate”.

Most recently saw the release (during the EPSC conference in Nantes) of results detailing the observation of re-forming ice layers on the surface of the comet

http://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/09/29/an-update-on-comet-67pc-gs-water-ice-cycle/

Here we have shown that sublimation conintues in the subsurface but stops at the surface when the surface moves into darkness, so we see a repeating pattern of ice formation on the surface, fuelling the coma. In addition, based on observations of the highly layered surface, we have shown the origin of the dusk shape of the comet which was generated by the low velocity impact of two cometessimal objects. We consider these layers to be like the layers of an onion, and using this analogy, you can consider that we have two similar onions (so two smaller comets that formed in a similar location) that have gently impacted one another to form the duck.

http://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2015/09/28/how-rosettas-comet-got-its-shape/

In the next months we are starting to plan out what we will do for the duration of the rest of the mission, in particular how we will, in September 2016, de-orbit Rosetta and crash land on the comet!. Part of these plans include flying into the tail of the comet , to investigate the plasma interactions there, as well as imaging the nightside of the comet and the coma.As I said last time, stay tuned to the Rosetta blog.

And the Rosetta twitter feed, maybe even follow me, but its not as scientifically interesting (especially my interactions with @iamcomet67p).

Matt, congratulations with the award you won. Great performance! Oh and thanx for the update on 67P, Rosetta and Philae. Work keeps going on, at least till september 2016, so we hope to see your next updates on the comet and the research of it. 🙂

Oh by the way, speaking of Brian May (in the video and also in your blog): we are trying to get him to the Netherlands for having a lecture on astronomy. Are you joining us in our efforts?

Hear f…ing hear!!!!!

Wow Matt, the award it’s a beauty. Usually awards look pretty awfull.

Btw what’s wrong with the microphone…or was it the speakers?

Inderdaad, er is een link, de geluidsinstallatie doet et al net zo goed als het Nederlands elftal 🙂

Hoe komt een engelsman op deze site terecht?

We hebben hem gevraagd en hij vond het een eer te mogen doen.

“de-orbit Rosetta and crash land on the comet!”

Why do they want to have it crashed to the comet and not leave it to orbit? Is there a scientific purpose for that?

I think they want to do the same thing as the probe NEAR Shoemaker did on the asteroid EROS, a soft, originally not planned landing: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NEAR_Shoemaker#Orbits_and_landing

The music of your introduction on the video: Rainbow? (love it)

I know Brian is very busy, maybe next year will be less busy. I am interested in having him visit.

The sound in the video is not so good , but it was when i was there 🙂

As for the end of mission, the discussion was balancing science output. We could have put the spacecraft in hibernation, but that would have been a longer hibernation than before (as the spacecraft is now on the same trajectory as the comet) and so colder. We have a limited amount of fuel and the instruments were only designed to run for the nominal mission, as they wear out or have consumables. The same goes for the spacecraft. We are confident that they will run ok for the extension, but another hibernation and exit would have stretched this capability, so we would have had a depleted instrument payload and operable platform for sure. For example ,with minimal fuel , the capability of the spacecraft to manoeuvre would have been MUCH reduced. SO, instead, we use the spacecraft and its fuel while we have the maximum capability on the spacecraft and instruments AND we get as close as we can to the surface of the comet, enabling measurements that would no be possible if we were not to crash the spacecraft into the comet.